Made for Austrian television in 1997 - the same year that he would make his feature Funny Games - Michael Haneke’s adaptation of Franz Kafka’s ‘Das Schloss’ sees the director working with adapted material that chimes entirely with a personal worldview we have come to know from films like The Seventh Continent, Code Unknown and Hidden (Caché), depicting individuals buckling under the increasingly cold and uncaring mechanical progress of modern society. Using many of the same actors who feature in Funny Games, it presents an intriguing parallel to the director’s breakthrough feature film.

Kafka’s unfinished novel ‘Das Schloss’, follows the activity of one such alienated individual trying to make sense of the innumerable and unfathomable levels of bureaucracy to find his own place and position in the world. K. (Ulrich Mühe) arrives in the village that surrounds the Castle as a stranger. Finding an inn, he is unable to obtain a room, but the innkeeper allows him to sleep on a mattress in the parlour of the bar. His intrusion is seen as unwelcome and Schwarzer, the son of the under-Castellan, challenges him, regarding him as a vagabond. A quick call however reveals that K. has been engaged by the Castle as a Land Surveyor. Frustrated in attempting to get any surveying done, and saddled with two hopelessly idiotic assistants, Arthur and Jeremiah , K. grudgingly accepts an appointment as school janitor, a position that is equally useless to the village. Desperately trying to get in contact with the Castle, K. suffers through a series of increasingly degrading experiences, but because he has spent all his money coming to the Castle, he finds himself unable to leave.

THE ADAPTATION

digitallyOBSESSED.com:

Franz Kafka famously requested that all his writings be burned, but his executors declined to do so, instead arranging for their publication. While this decision has been the source of consternation to generations of students perplexed by Kafka's descent into surrealism and nightmarish bureaucracy, it's certainly indisputable that Kafka more than any other writer captured the grim and often ludicrous reality of modern life, with nonsensical rules, petty bureaucrats, and inexplicable personal grudges that buffet people about uncontrollably. One of the finest examples is his unfinished novel Das Schloss, which was faithfully brought to European television in this adaptation by Michael Haneke.

Kafka left a number of gaps in the prose narrative, which are represented here by blackouts; they become increasingly frequent as the film progresses, to the point where it is quite choppy and almost composed of brief vignettes surrounded by black. Finally, the movie breaks off mid-sentence, just as does Kafka's fragment. The result will prove nearly as frustrating and unsatisfying as reading the novel, with no resolution and K. seemingly trapped in a peculiar existence that shifts on him from moment to moment. Haneke offers no suggestions as to where Kafka might have gone, merely ending abruptly with a title card. The translation of novel to screen is often quite literal, with music being heard only as an accordion band plays in the tavern, keeping an austere formality to the proceedings and denying one of the cinematic concessions that are routinely made to literary adaptations.

REVIEWS

dvdtimes.co.uk:

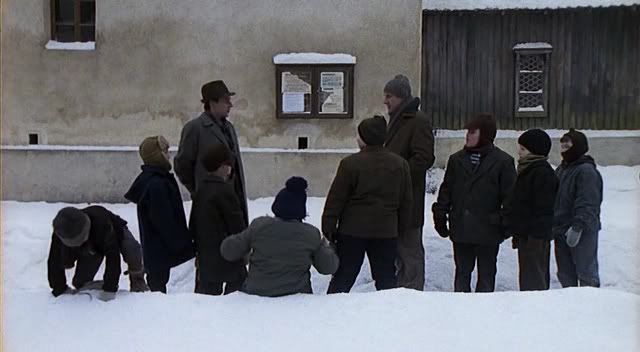

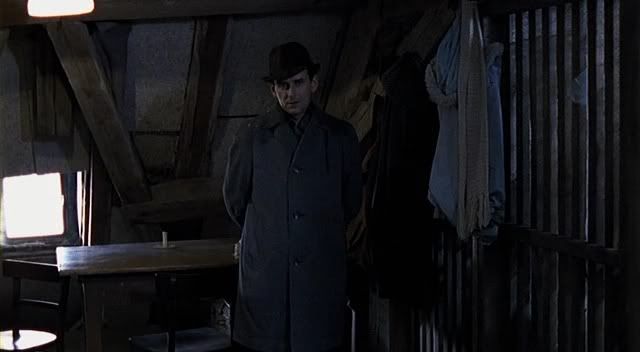

As would be expected from the director at this point in his career, Haneke’s now familiar style is appropriate to the subject, adopting a neutral approach marked out by jump cuts to black screens. The gaps however are not Kafka’s - The Castle is perhaps the writer’s most fluid and consistent work, and only incomplete in that it never reached a conclusion. Haneke however makes use of his trademark method here rather to cut back on the length of certain scenes, excising a number of minor characters and reducing others - the landlady’s role is greatly reduced and it removes many of her and K.’s cross-purpose confrontations - but it matches the curious elliptical rhythms and the dreamlike passing of immeasurable periods of time in Kafka’s novel. Haneke of course fully exploits the fact that the novel is open and unfinished – as most of his own films are – taking pleasure in bringing the film to an unexpected conclusion as the end of the manuscript, even though it is not the one (again featuring the landlady) that finishes the novel. Haneke’s way of showing K. attempting to make headway against the constant grind of the machinery of bureaucracy and the petty social hierarchy, is to show him trudging repeatedly back and forth through the snow and howling winds, often in the dark – waiting for the smallest scrap of information or news from the Castle, that they have need of him or at least recognition of him.

It’s a perfectly adequate way to depict Kafka’s struggle of the individual to find their place in society, but it’s also a failure, as is any attempt to capture the essence of Kafka on the screen. The best any director can do with Kafka’s absurd, nightmarish and unfilmable works is find elements from them to incorporate into their own worldview - as in Soderbergh’s fun-but-missing-the-point Kafka – or vice-versa, as in Orson Welles’ ambitious, often impressive, but ultimately doomed adaptation and re-writing of The Trial. Haneke’s adaptation of The Castle is more literal and faithful to Kafka than either of those films, but he never makes it come alive or personal in the way that he can usually lift a storyline off the screen and into your own life. A narrator is used to maintain some of the authorial musings on the characters and their behaviour, but more often Haneke depicts events with neutrality and lack of comment, which allows him to capture Kafka’s sense of the absurdity of social behaviour, but fails to capture the complexity of the characters’ deeper striving for belonging and spiritual meaning. Haneke would achieve this element of humanity much more successfully in Time Of The Wolf, but, perhaps through the necessity of adaptation and simplification for television, he fails to do so here.

digitallyOBSESSED.com:

Haneke emphasizes several aspects of Kafka's story to good effect. Obviously, without faceless bureaucrats who thoughtlessly play with the fates of ordinary people, it would hardly be a Kafka work. Klamm is never seen or even heard, other than a brief shot of his carriage pulling away from a distraught K., and even his secretaries are barely glimpsed. The politics of the village, and even moreso the Castle itself, are built entirely around suspicion, prostitution, and informing. As a result, the alliances are constantliy shifting, which makes the heedless and uncomprehending K. particularly vulnerable. But perhaps the most frightening aspect is how easily the villagers have accepted this way of life, and how fast K. begins to become acclimated to the manipulations that it involves. But Kafka isn't all grimness; he has a darkly comic side that is exemplified best here by the two inept assistants, both dependent on K. and treacherous whenever the opportunity presents itself. While they're only in the way and don't know the first thing about surveying (not as if it makes any difference when there is no surveying to be done), K. finds himself unable to reject them completely for quite a while; the result of their dismissal is a dichotomy, as Arthur becomes even more servile and Jeremiah quickly moves in to take Frieda as his own.

Mühe does a fine job of portraying K. as an exhausted man barely able to muster the anger at the system, but periodically lashing out ineffectually whenever the absurdity becomes too much. He rather reminds me of Brazil's Sam Lowry, struggling against a world that is uninterested in anything other than maneuvering for position (not least of all because Mühe rather resembles Jonathan Pryce). Lothar is intriguing as the fickle Frieda, projecting a needy sensuality without being traditionally attractive (a matter commented upon by her chief rival for the barmaid position of honor). Without an ending, however, the movie suffers from an aimlessness that is traceable to Kafka; without knowing where it's going, and thus what really needs to be emphasized, it remains a truncated torso that can at best be intriguing in its possibilities. One of the best sequences in the picture is K.'s interview with the Superintendent (Paryla), who sends his wife and the two assistants on an impossible task of finding a particular paper in a morass of documents, while telling the elaborately nonsensical tale of how K. came to be appointed land surveyor for a village that needs no surveying. Full of obscure references and incidents that emphasize the random haplessness of K.'s position, it's also hilariously comic as the search continues unabated in the background. Comedy and the clumsiness of bureaucracy are beautifully distilled into an essence of Kafka, blending tragedy and ridiculousness in equal parts.

http://rapidshare.com/files/170700114/Das_Schloss.part1.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/170716992/Das_Schloss.part2.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/170943888/Das_Schloss.part3.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/170971296/Das_Schloss.part4.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/170997067/Das_Schloss.part5.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/171016684/Das_Schloss.part6.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/171027813/Das_Schloss.part7.rar

Rar Password: www.surrealmoviez.info

0 comments:

Post a Comment